The Ambrosian Library

- Amy Unfried

- May 2, 2019

- 3 min read

For our second (and last) morning in Milan, we visited the Ambrosian Library, a research and cultural center founded in 1607 that is one of the highly-rated cultural institutions in the city-- both an art museum and a library.

The featured exhibition, of which parts were in each of the museum and library portions of the building, was of Leonardo da Vinci's Atlantic Codex. (The name has nothing to do with the Atlantic Ocean but instead refers to the name of the size of the paper used for binding the codex.)

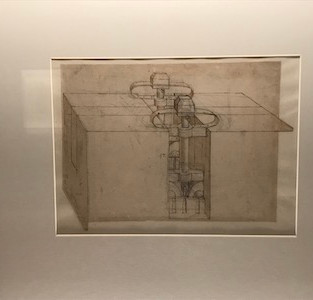

The codex has been unbound and remounted for reasons having to do with both conservation and display. Here are some sample pages, with pen and ink drawings by Leonardo showing a machine for stamping objects such as buttons, and an "assault machine" that would be "composed of a mobile carriage equipped with a ladder and a horizontal covered bridge allowing one to invade the enemy fortress in complete safety."

In another area, there was an exhibition of Raphael's cartoon for "The School of Athens," the fresco in the Vatican Museum. The cartoon is the detailed drawing perforated with holes by means of which the design was transferred to the wall to be frescoed. There was a good explanatory film in one area, and the cartoon itself in the room behind it. As works on paper, especially of that age, are very fragile and precious, the lighting was very low, as was the case with the Leonardo drawings.

In fact I was impressed with the attention paid to the lighting of all the potentially vulnerable media (not the sculpture, mosaics, jewelry, or ceramics), and I conjecture that the sensitivities of those on the library side of the institution to the hazards presented by light may have increased the sensitivities of those on the museum side, since in most other museums I have not noticed such care except with respect to works on paper. Here in many rooms, the light was managed in such a way as to light each painting well enpough to present no difficulty to the viewer, but no unnecessary additional light bounced around the walls and other surfaces. It probably saves them a lot of electricity consumption too; and perhaps that is indeed the primary motivation.

I took pictures of a great many works, far too many to include here, especially as I am trying to catch up with the activities of the past couple of days. Two, though, I must mention as particularly having caught my attention.

This one is Bramantino's "Adoration of the Baby" (ca. 1485), which I found arresting for the stiff, unnatural (but consistent!) poses of all the adorers, and for the mystifying female figure at right, and especially for the equally mystifying quartet of musicians with assorted odd instruments performing in the background.

The other is by Ambrosio Bergognone and depicts our old friend St. Peter Martyr in the company of St. Christopher. When we stayed in Milan in 2011 for two months, many of the churches and museums we visited at that time had depictions of St. Peter Martyr, of whom I had never heard until then. He was a real person, unlike the legendary St. Christopher, and, as faithful readers with really good memories for religious trivia may recall, he was a Dominican friar in Verona in the thirteenth century. For complicated reasons of church politics, he was assassinated in 1252 by the unusual method of being struck on the head with a sword, and he is depicted in art with the sword embedded in his head. (Sometimes, if that would be too distracting from other elements of a picture, he just has a bloody gash in his head.) Here, the sword is fairly short but definitely present.

Comments